In the world of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, the job of the firemen is to burn books. Because in a totalitarian society, nothing is more dangerous than a conscious citizen:

“A book is a loaded gun in the house next door…Who knows who might be the target of the well-read man?”

Another aspect of books is the spread of words and therefore thoughts and ideas. In George Orwell’s 1984, Newspeak was the method employed to combat this threat to the autocracy:

“…the whole aim of Newspeak is to narrow the range of thought. In the end we shall make thoughtcrime literally impossible, because there will be no words in which to express it. “

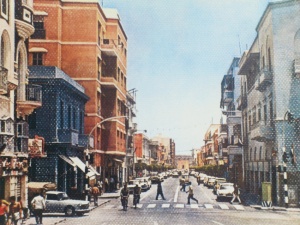

Oppressive dictators think alike, and Libya’s former tyrant was no different. In order to keep a leash on the minds of the people, Gadhafi abolished Libya’s previous culture, replacing it instead with an engineered image of him as saviour of the country (and indeed, of Africa in general). It wouldn’t do to have other heroes, which is why the shrine of Omar Mukhtar in Benghazi was demolished. Nor it would be prudent to read anything other than what Gadhafi says or approves of, which led to systematic control and censorship of speech.

Many writers were imprisoned, tortured and/or killed. Libraries and cultural centers were shut down, turned instead into “mathabat” , meeting halls for Gadhafi’s thugs. Publishing companies were shut down, replaced by state owned ones. His “green book” was taught as gospel in schools and university. What few newspapers, radio stations and television channels existed were all controlled by the regime. Writing in Libya was a dangerous profession.

So it’s no surprise that when the revolution happened, a tidal wave of words, both written and spoken, washed over the country. The opinions and beliefs that everyone had secretly held were finally uttered, hindered no more by the regimes’ wall of silence. In Benghazi alone over 100 magazines and newspapers were founded, because everyone had something to say. Books were published about the regime, channels and radio stations were established.

This wave of words has ebbed since then. Most people now use Facebook to express themselves, but this isn’t without its consequences. Rumors and fear-mongering are a prominent feature on social media and Libyan press agencies. We’re still learning the privileges and repercussions that freedom of speech gives us.

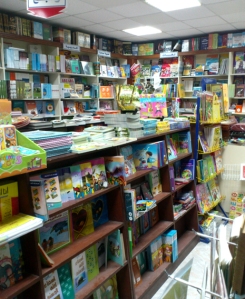

The literature situation is still rather dismal. In Benghazi there’s only a handful of bookstores, with limited selections available. Tripoli is better in this regard, but only slightly. Many have said that Libya is not a nation that likes reading, but there is evidence that indicates the contrary.

A used-book fair was held in both Tripoli and Benghazi, with an unexpected turnout. From this article on the fair:

One visitor, clutching a novel and a volume of poetry, said that there were so many people at the fair, it was quite overwhelming. “I had the impression that Libyans are not readers,” she said, “so I am very surprised.”

But with limited resources it will still be difficult to encourage the newer generations to read. This is partially the reason why I started The Young Writers of Benghazi. Encouraging aspiring writers and producing literature on a local level will give us the chance to showcase the literary talents in Libya, tackle issues that directly pertain to our culture and society (as opposed to importing books), and will give Libyan literature a chance to flourish. So far the support we’ve gotten and the talent we’ve seen among Benghazi’s students have been incredible.

My first exposure to Libyan literature came when I read “In The Country of Men” by Hisham Matar. It’s a captivating book about the life of a boy with a dissident father, growing up in Gadhafi’s Libya. I had read it before the revolution, and seeing the same emotions about the tyranny that I felt written down before me was a new experience. I knew that most Libyans felt the same way, but were too afraid to voice it.

Further research into Libya’s literature revealed a side of our culture I was unaware of. There were writers and poets, both young and old, who had received recognition outside the country. Sadeq Neihoum, Ibrahim Al-Koni and Hisham Matar are just a few of those with incredible writing that we are largely unaware of.

Famous Libyan Writers, from left to right, top to bottom: Al-Sadeg Al-Neihoum, Ibrahim Al-Koni, Khalifa Al-Fakhri, Khalifa Al-Tellisi, Wahbi Al-Bouri, Ahmed Al-Faqih and Sa’eed Sifow

Supporting local writers, poets and journalists will strengthen our culture. It’s imperative for Libyans to turn to books and other forms of the written word to fortify their own thoughts and protect their newly gained freedom of speech. Just as the absence of books and knowledge strengthens a dictatorship, their propagation will strengthen our democracy.

I appreciate your effort to encourage the young talented writers to write in Benghazi. It’s amazing seen people encourage a hidden part of our society.

Thank you so much, I really appreciate it! 🙂

I once angered a group of people by stating that the world would be better off without the newspaper. I now have to include the internet. We would be better off not knowing and staying in the cocoon of ignorance. Rights would be taken away but we would not know it.

This is interesting insight into an age-old issue that has affected many countries. It truly is sad how many wonderful writers get lost in the fray of control. Books are power, and those who want to control power do whatever they can to eliminate our cultural consciousness of it. Great post!

Wow, thanks for sharing!

Very well written!

Reblogged this on victormiguelvelasquez.

Good writing………….well said……… nice to share this……….

#wordpress!

I don’t if it’s the same thing but this reminds me of how Cambodian intellectuals were killed in the ’90s I believe.

Great post! I just wrote a blog the other day about the influence of books and libraries on my life. There is a reason that tyrants ban books, literature, and learning. Knowledge really IS power!! @blendedfamilychaos

your way of writing really inspires me… thanks for sharing such a beautiful post… i hope you will entertained by visiting http://mindtechnorms.wordpress.com

Reblogged this on haitianbarbiek.

Dictatorships work on remaking the national identity. It’s so disheartening to see how across the islamic world Heritage sites are targets for autocratic puppet regimes, like why, are they so dangerous. Always remember Gaddafi was furthering the interest of dominant powers who still seek to conquor the Arab Muslim mind. Great initiative.

Reblogged this on a fiercely gentle approach.

Reblogged this on dunjav.

Great job and really interesting! Visit my New blog, hope you like it! 😊

Thank you for your blog. Keep at it.

Great Story……All the Best !

You have whetted my appetite for Libyan literature, and I will be seeking it out now. Possibly reviewing on blog. So, thanks.

Orwell knew what he was talking about with Newspeak, didn’t he? I suppose his novel parallels quite a few African countries. Anyone who wants to hear more about literature, fiction and creative writing please do visit my blog HERE http://theartofwritingfiction.wordpress.com/

Reblogged this on perk2911.

Beautiful post! You’re doing wonderful, inspiring work.

Pingback: What It Means To Be Libyan | Journal of a Revolution

Pingback: 2015: A Year of Great Blogging | The Daily Post